Marietta Earthworks

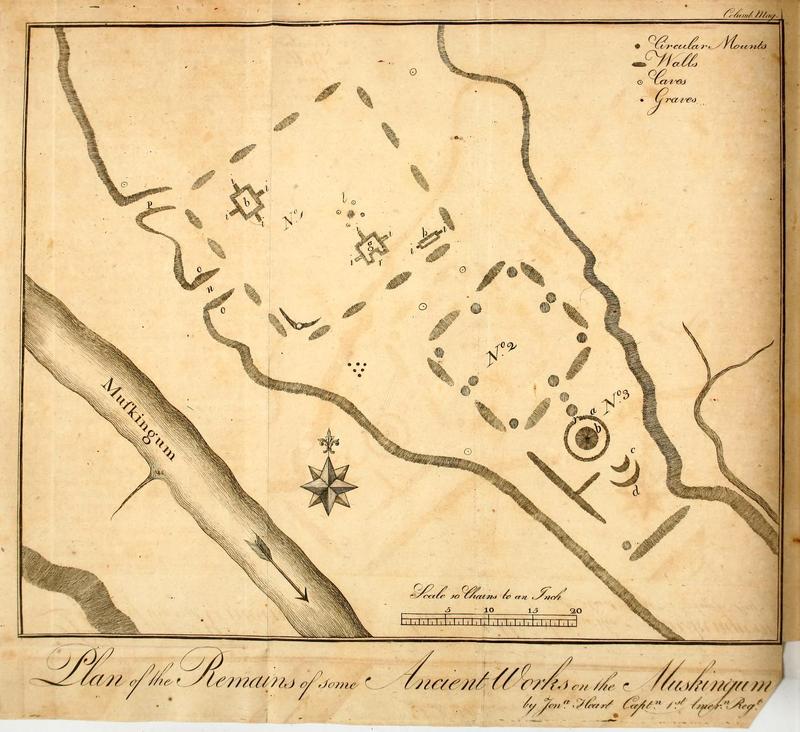

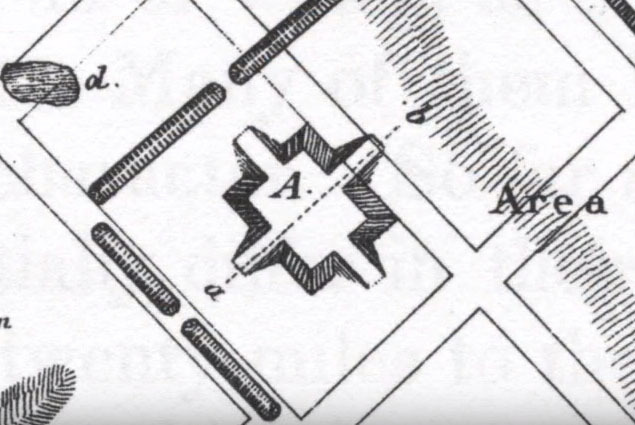

The Marietta Earthworks is the largest earthwork complex in the eastern half of southern Ohio. Built during the Late Adena and Hopewell cultures and located on a terrace above the Muskigum river, its elaborate structures included a ringed burial mound (Conus Mound), two large rectangular enclosures (one of which is now lost, the other survives as part of Quadranaou Mound), two platform mounds (Capitolum and Quadranaou Mounds), and a ceremonial, graded walkway down to the river (now lost). Archaeologists suggest that the complex was used for c. 1,000 years for ceremonial purposes before being abandoned.

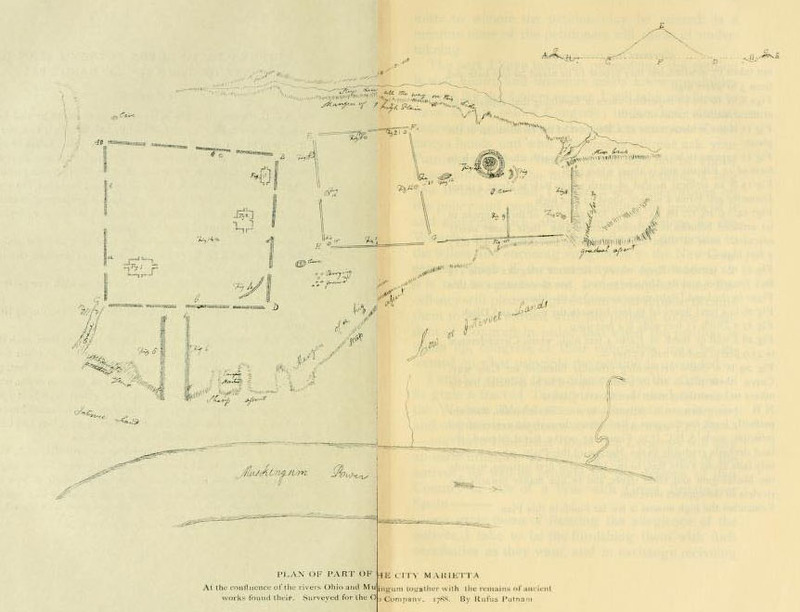

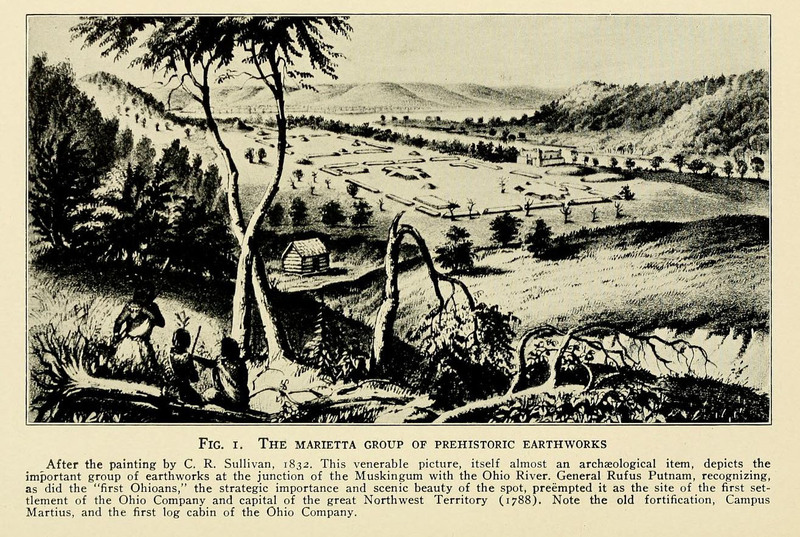

The survival of so much of the original earthworks is due to the unusually respectful attitude of the first European settlers in Marietta who created the earliest recorded preservation law west of the Appalachians. After the Revolutionary War, the “Ohio Company of Associates” was formed and led by Rufus Putnam, Benjamin Tupper, and the Reverend Manasseh Cutler, all of whom sanctioned the purchase of land along the Ohio River. Veteran officers of the Revolutionary War were given tracts of this land instead of cash for their war efforts: George Washington wrote in approval that “no colony in America was ever settled under such favorable auspices.” Captain James Heart's map of the earthworks, published in 1787, only furthered public enthusiasm.

In 1788, Putnam journeyed with the first installment of men down to the present site of Marietta, named in honor of Marie Antoinette. Upon first sight of the mounds, Putnam wrote that those who had built them were people of “ingenuity, industry, and elegance”, and believed them to have been built for defensive purposes. These first Marietta settlers carefully attempted to plan their new settlement around, rather than over, the mounds, and local interest soon demanded further inspection of the earthworks.

The Reverend Manasseh Cutler was the first to rigorously examine the surviving structures, and his eyewitness accounts are important evidence as to their original layout and appearance.

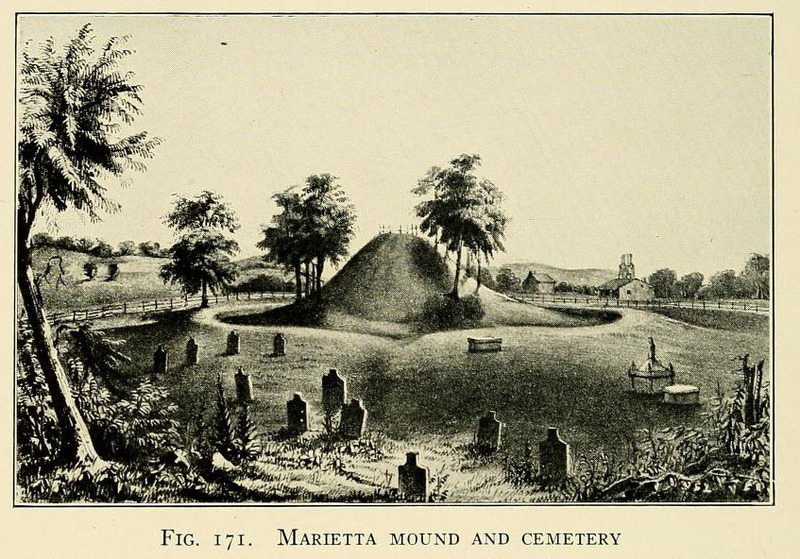

Conus Mound, 30 ft in height, is one of the best surviving ditch-and-ring burial mounds created by the Adena culture. At one point, the wall and ditch merge to become an earthen bridge, signaling the entryway. Of this mound, Cutler wrote:

“An opening being made at the summit of the great mound, there were found the bones of an adult in a horizontal position, covered with a flat stone. Beneath this skeleton were three stones placed vertically at small and different distances, but no bones were discovered. That this venerable monument might not be defaced, the opening was closed without further search.”

Quadranaou mound is undoubtedly the largest and best-preserved of the surviving Marietta mounds. Built to a rectangular form, it stands 10 ft. tall and almost 200 ft in length. The Reverend Manasseh Cutler, in his exploration, chose to attempt an early form of dendrochronology:

“When I arrived, the ground was in part cleared, but many large trees remained on the walls and mounds. The only possible data for forming any possible conjecture respecting the antiquity of these works, I conceived must be derived from the growth upon them. By the concentric circles, each of which denotes the annual growth, the age of the trees might be ascertained.”

Although he made a noble effort, and counted c. 900 tree rings, the earthworks were built c. 1,000 years earlier than he determined.

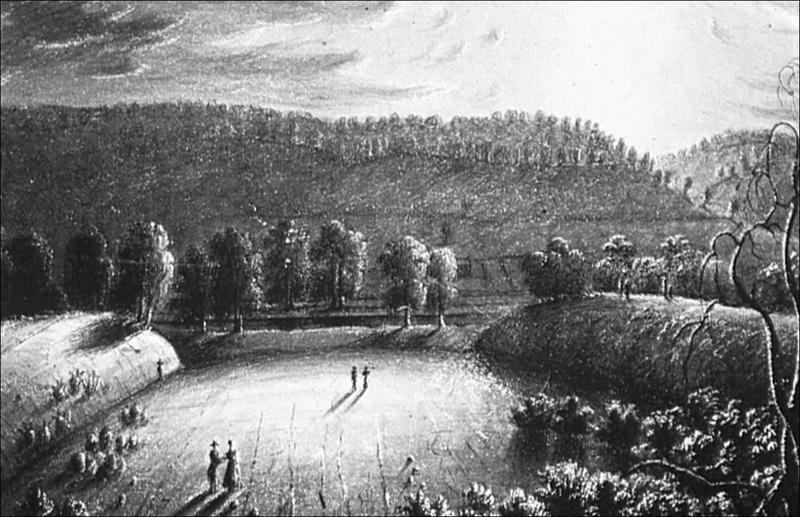

Unfortunately, although the Sacra Via, whose width runs to 150 ft wide, still survives as part of a public park, the magnificent 20-ft high earthen walls which once lined the walkway were removed in 1843 to be turned into bricks. Such walkways were typical of many ceremonial earthworks. The walkway’s central axis was aligned with the winter solstice sunset, marking yet another instance in which the Hopewell carefully attuned their earthworks to astronomical occasions.