Middle Woodland Period - The Hopewell Culture

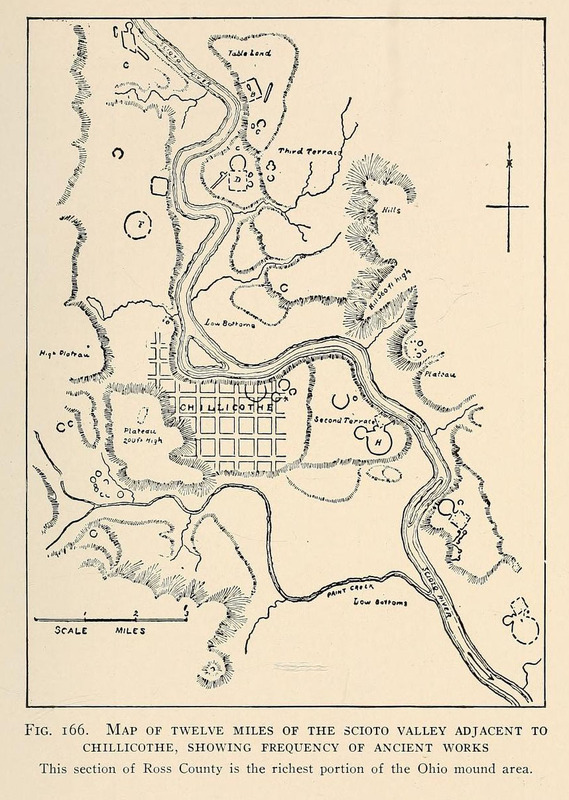

The Middle Woodland period, which lasted from roughly 100 B.C. to 400 A.D., is perhaps best known in the Ohio River Valley as the era during which the Hopewell culture flourished. The basic traits which define the Hopewell culture are: more elaborate burial practices, larger and more complex earthworks which tended to grow horizontally rather than vertically over time; a greater variety of exotic material obtained through national trade networks; and a more complex artistic style than the Adena period.

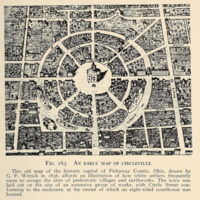

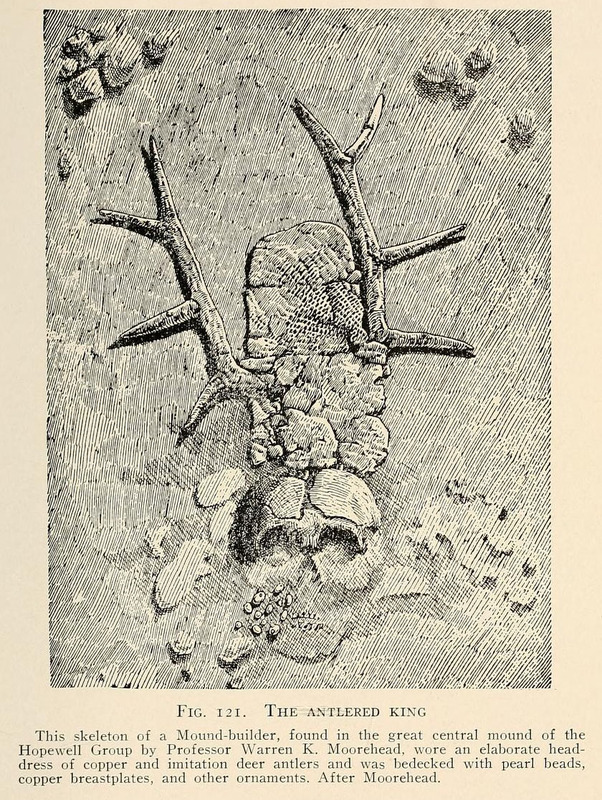

Although the term “Hopewell” is used to describe many contemporary peoples throughout all of Eastern North America during the Middle Woodland, the Ohio Hopewell are regarded by most archaeologists to be the most extraordinary of all these various peoples. The Hopewell culture was named after Warren K. Moorehead’s excavations on farmland owned by Mordecai ‘Cloud’ Hopewell in Chillicothe to provide exhibits for Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition of 1893.

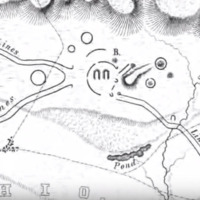

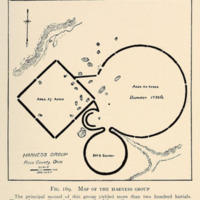

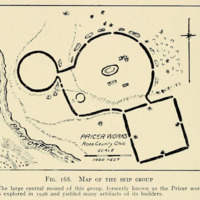

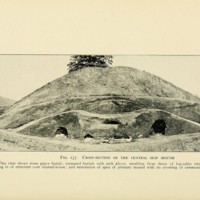

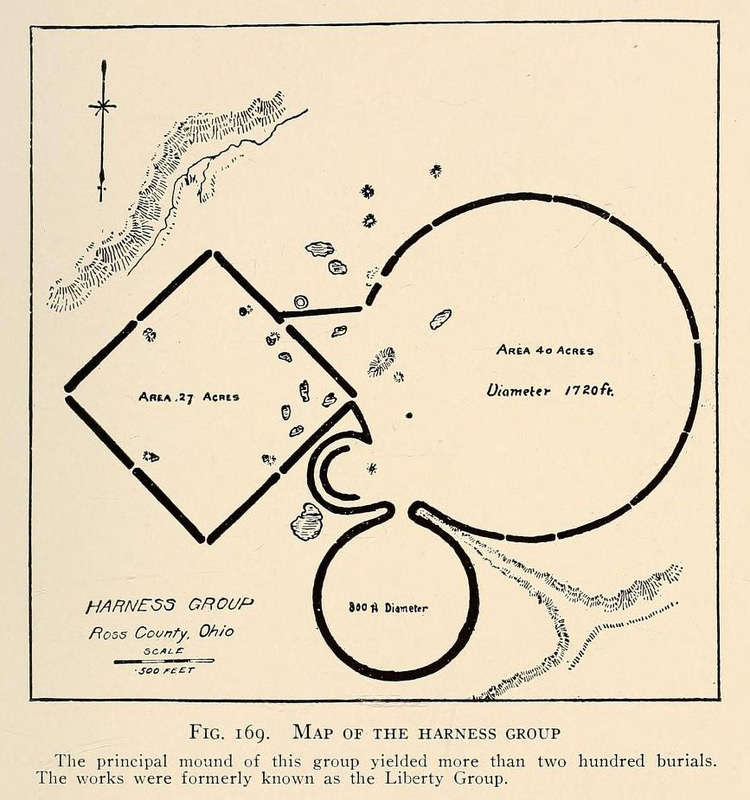

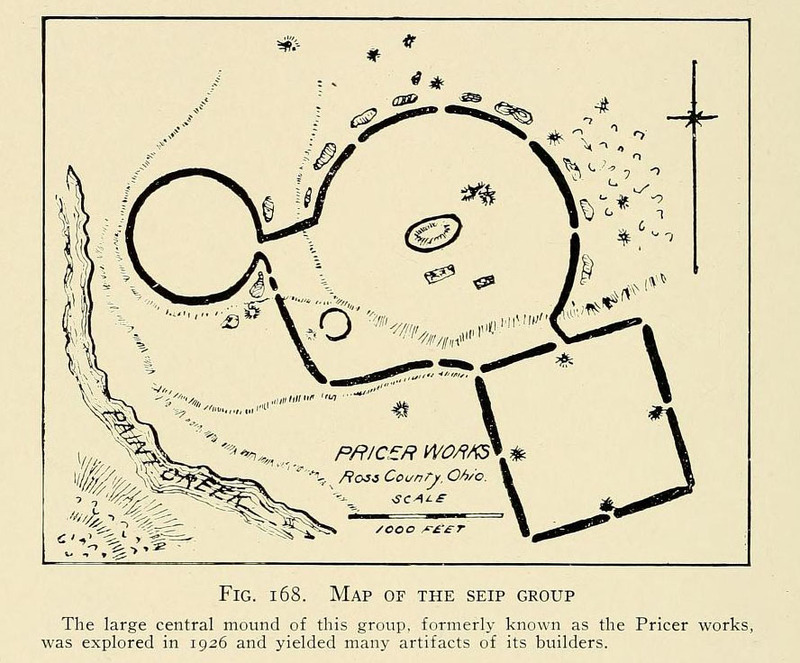

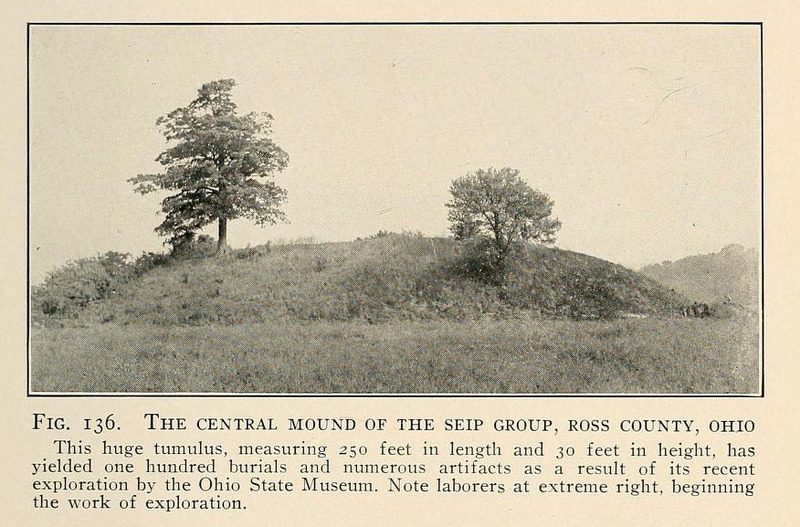

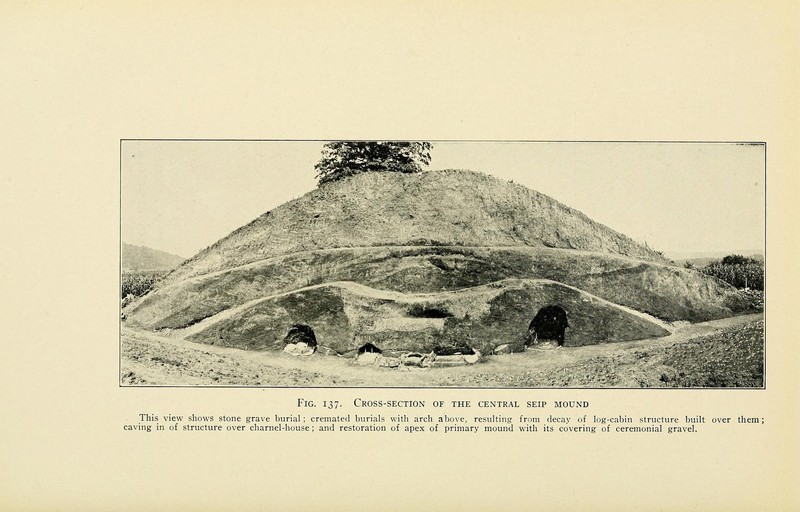

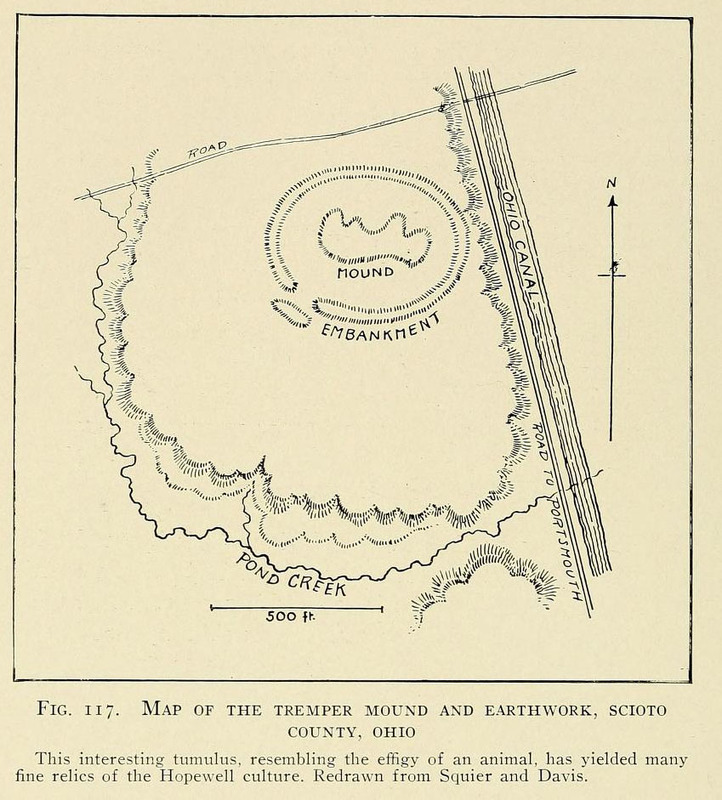

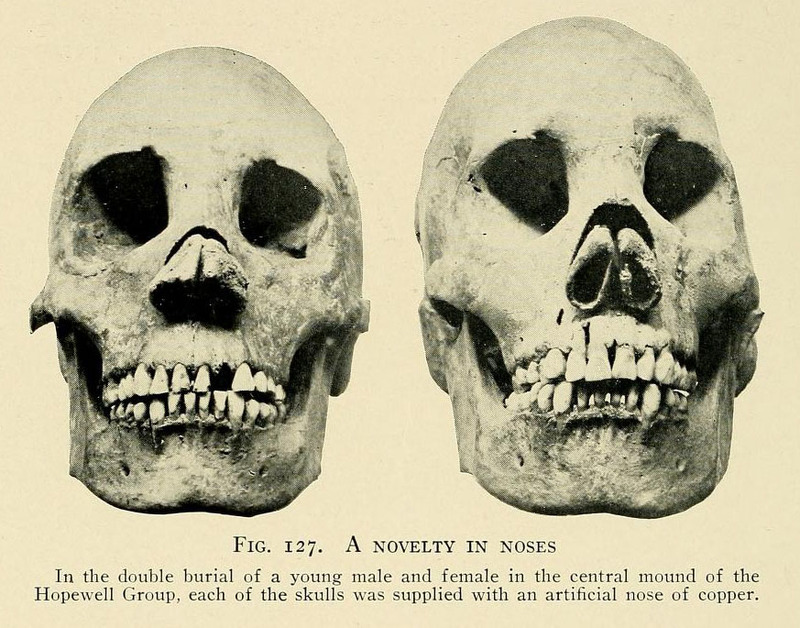

Like their Adena predecessors, the Hopewell culture built monumental and intricate earthworks which still astound archaeologists. Whereas the Adena buried their dead upon the bones of their ancestors, thus building their mounds vertically, the Hopewell moved away from extreme verticality and built their mounds horizontally. Generally, the Hopewell viewed their earthworks more typically as ceremonial centers. Although some earthworks were still used as mortuary sites, with associated conical burial mounds, the dead were more likely to be cremated and not always stacked atop each other in succession.

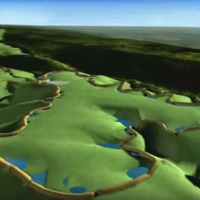

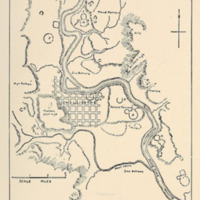

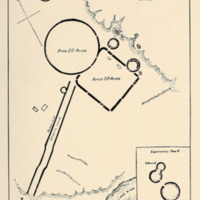

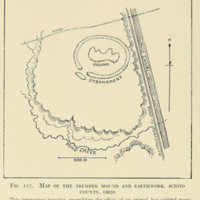

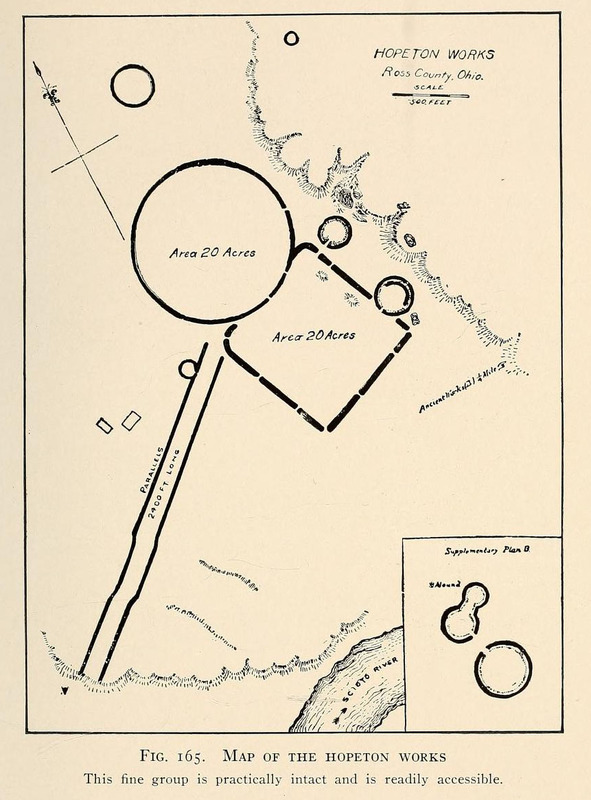

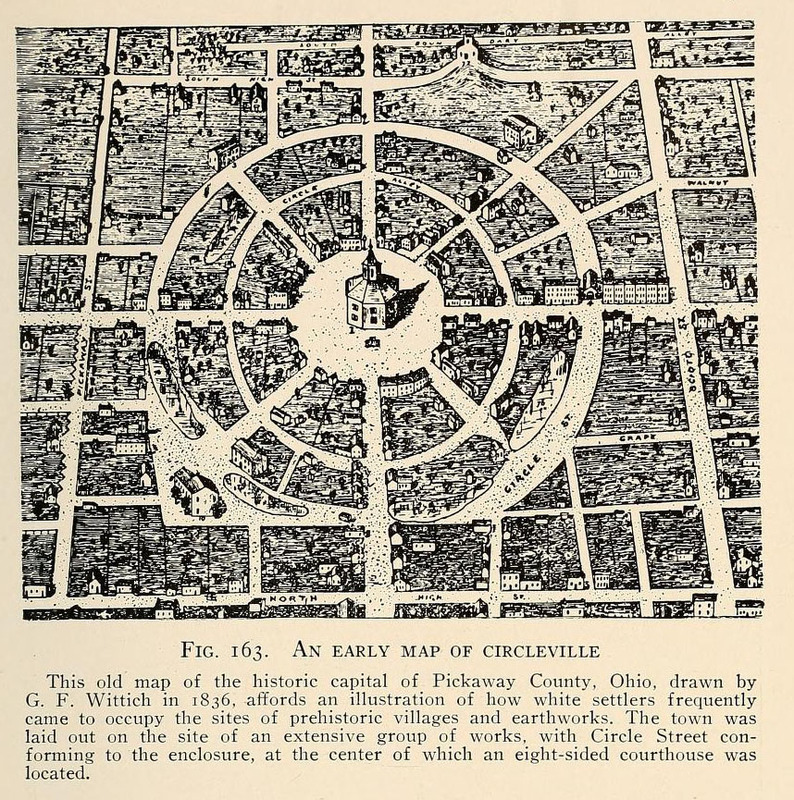

Two types of earthworks were particular Hopewellian favorites: geometric earthworks, often extremely large, and hilltop enclosures, which usually followed the contours of the landscape and were consequently often irregular in shape. Proportionally, geometric earthworks survive in greater numbers and seem, on the whole, to have been constructed more than hilltop enclosures. Such earthworks were often built in squares, circles, or, more rarely, octagons. The precision with which earthworks were typically built underlines the Hopewell culture’s intense familiarity with geometry and mathematics, and indicates that they created their own measuring system. Astronomy often played a particularly important role in the construction of earthworks, with many, such as Newark Earthworks, aligned to interact with solar or lunar movements.

Within the Hopewell culture, hilltop enclosures seem to have been a predominantly southwestern Ohio tradition. Great earthen walls, often reinforced with stone, were constructed around artificially flattened hilltops, often with specially constructed wells to catch rainwater for ceremonial purposes. Initially, archaeologists of the nineteenth century assumed such structures were defensive, and indeed many remaining sites are often called “forts”, but archaeologists today largely believe the enclosures were purely ceremonial. It is possible that such large ceremonial creations served as pilgrimage sites which united the diverse cultures of Ohio, and possibly beyond, and helped increase the demand for trade among cultures as they came into contact with each other.

The Hopewell culture vastly extended the trading infrastructure which the Adena culture had utilized. Some of the materials they acquired included copper from the upper Great Lakes; mica from the Carolinas; pearls, shells and alligator teeth from the Gulf of Mexico; galena, pipestone, flint, grizzly bear teeth, obsidian, and chalcedony flint from Illinois and Missouri; steatite; silver; hematite; and obsidian from the Rocky Mountains. Archaeologists still debate what reciprocal gifts the Hopewell exchanged; Flint Ridge flint from Ohio, with its characteristic swirled appearance, has been found in other areas of the United States but not in enough quantity to suggest a heavy trade. It is possible that, because many Hopewell earthworks seem to have been centers of pilgrimage and religious worship, the Ohio Hopewell traded knowledge and advice in return for material gifts.

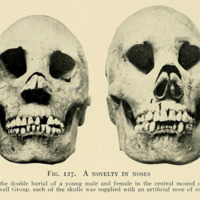

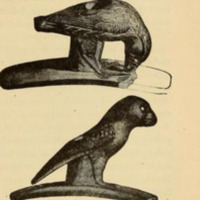

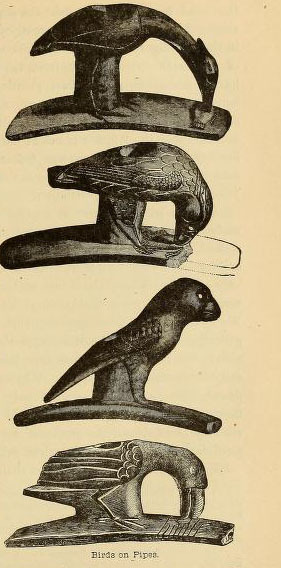

Acquired materials were incorporated into elegant artworks. Hopewell art is characterized by an intricate use of positive and negative space; mirror symmetry; curvaceous or geometrical shapes; a seemingly increased use of animal motifs, particularly those of deer, bears, and birds; and, in pottery, thinner and more refined usage and new shapes such as bowls and jars, though the stacked coil preparation method was still utilized. The human form was a rare depiction in Hopewell art.

The Hopewell were more sedentary than the Adena and continued and extended the Eastern Agricultural Complex by expanding the range of crops grown, including tobacco, but still maintained the framework of a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

By A.D. 400, the Hopewell culture and its earthwork building were all but over. What caused this is unknown, but there was a major shift in the succeeding Late Woodland period settlements and subsistence. People lived in larger villages often surrounded by walls or ditches. Corn became more important and the bow and arrow were introduced. Some archaeologists characterize the end of the Hopewell as a cultural collapse because of the abandonment of the monumental architecture and the diminishing importance of ritual, art, and trade. Yet the population seems to have increased and it simply may be that villages became more self-sustaining and inwardly focused.