Late Prehistoric Period - The Fort Ancient Culture

The Late Prehistoric period, from c. 1000 A.D. to 1650 A.D., was the last period before the arrival of Europeans into Ohio during the eighteenth century. The Fort Ancient culture was the last of the three Native American mound building cultures in the Ohio River Valley. This culture was so named because their type site, a village, was built near the Hopewell-era Fort Ancient site in Oregonia, Ohio.

The Fort Ancient peoples are generally thought to be descendants of Late Woodland predecessors, though some archaeologists suggest they may be related to the southeastern-American Mississippian culture, with whom they frequently traded and shared symbolism. The Fort Ancient culture is notable for: their effigy mounds; cultivation of corn and their use of modern farming techniques; their larger villages and increasingly sedentary lifestyle; and continued, if severely reduced, interaction with cultures across America.

Strictly speaking, the Fort Ancient culture was not a mound building culture in the same tradition as the Adena and Hopewell cultures before them. Mound building as a common cultural tradition had died out during the still poorly-known Late Woodland period. However, when needed, Fort Ancient builders tended to build small flat-topped mounds and animal-shaped effigy mounds. Occasionally, prior mounds from the Adena and Hopewell cultures were repurposed for ceremonies or burial places, although many burials were located at the center (or outskirts) of a village within flat graves, such as those at SunWatch Village, a reconstructed Fort Ancient village in Dayton, Ohio. Grave goods included ornaments, tools and pipes.

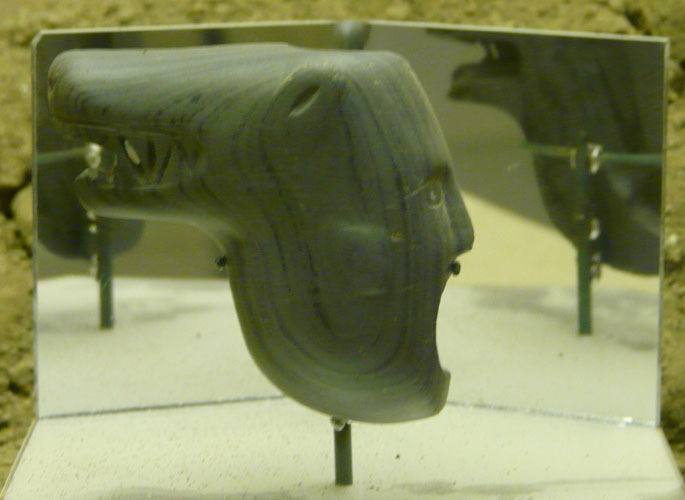

Although artwork became arguably less extravagant than under the Hopewell culture, the Fort Ancient continued the practice of effigy pipes and decorative pottery, still created by stacking clay coils atop each other. Bone tools were created, most often from white deer, and such items are found in relatively large numbers within surviving graves. Stone, pearls, and marine shells from the eastern and southern coasts were equally popular. Although trade became restricted, and the more communal atmosphere of the Hopewell era was replaced by more a village-specific mentality, the presence of exotic shells testifies to the continued interaction with other cultures, particularly the Mississippian culture.

The Fort Ancient culture is likely to have built Serpent Mound, in Peebles, Ohio (although some archaeologists propose it was constructed by the Adena culture), and Alligator Mound, in Granville, Ohio. These effigy mounds were not burial sites, but were probably more ritualistic in nature, serving as ceremonial sites. The “Alligator” of alligator mound was initially translated as such by early settlers, but several archaeologists now believe it to represent the Underwater Panther, a mystical creature which inhabited bodies of water.

By c. 1000 A.D., the growing popularity of corn transformed the Fort Ancients into an increasingly sedentary culture. The cultivation of beans and squash, pairing with corn to become the historic “three sisters” of Native American tradition, changed the Fort Ancient diet. Although meat remained popular, and hunting was made somewhat easier by the now-common use of the bow and arrow (introduced c. 700 A.D.), protein intake and diet diversity became alarmingly slim. Archaeologists at SunWatch Village have analyzed human bone samples using S.I.R.A (Stable Isotope Ratio Analysis) and have discovered that corn may have comprised more than half of the villagers' diet. Resulting dental trouble, spinal diseases, and osteo-related afflictions caused the quality of life to plummet.

Due to the increase in agricultural certainty, villages grew larger and more permanent, often occupied for 15-30 years with c. 100-500 occupants. Prime villages were often located in rich bottomlands by streams, though they remained semi-seasonal as hunting camps were still used in the winter.

The end of the Fort Ancient culture, and indeed many of the pre-historic native cultures, came with the settlement of Europeans in America. Unlike the eastern seaboard cultures, the Fort Ancient culture had no recorded direct contact with Europeans, and in fact disappeared relatively quickly c. 1650 A.D, long before the Ohio Valley was permanently settled by Europeans. The decline of the Fort Ancient culture remains unclear: although the theory of decimation by European disease remains popular, there is little direct evidence, nor is there direct evidence for conflict with another culture.

Regardless of the cause, the disappearance of the Fort Ancient culture signaled the end of a mound building tradition in the Ohio River Valley. The cultures which emigrated to the Ohio River Valley, most likely ancestors of the present-day Shawnee tribes, did not share a mound building tradition. Their encounters with European settlers, and their understandable inability to provide a history for the mounds, encouraged many Europeans in the unfair and incorrect opinion that the Native Americans could not have been responsible for the creation of the fine mounds which grace the Ohio River Valley.