Who Were the 'Mound Builders'?

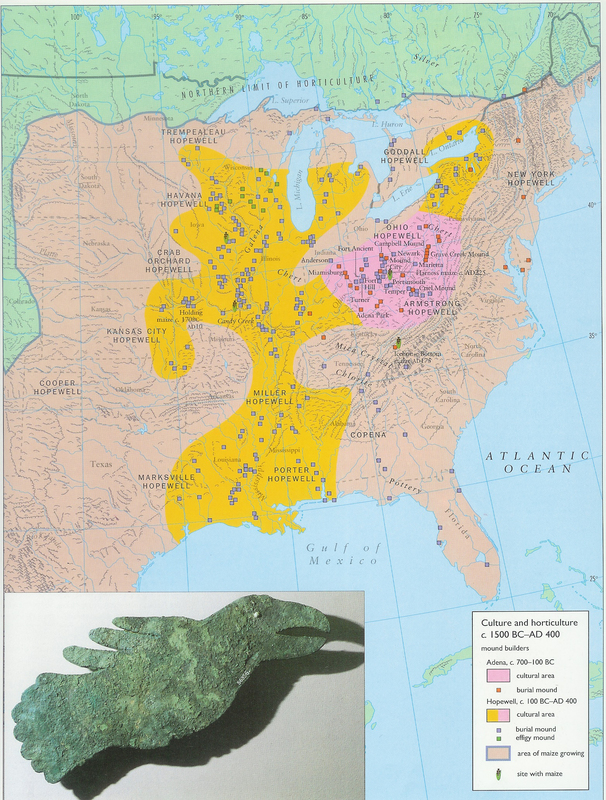

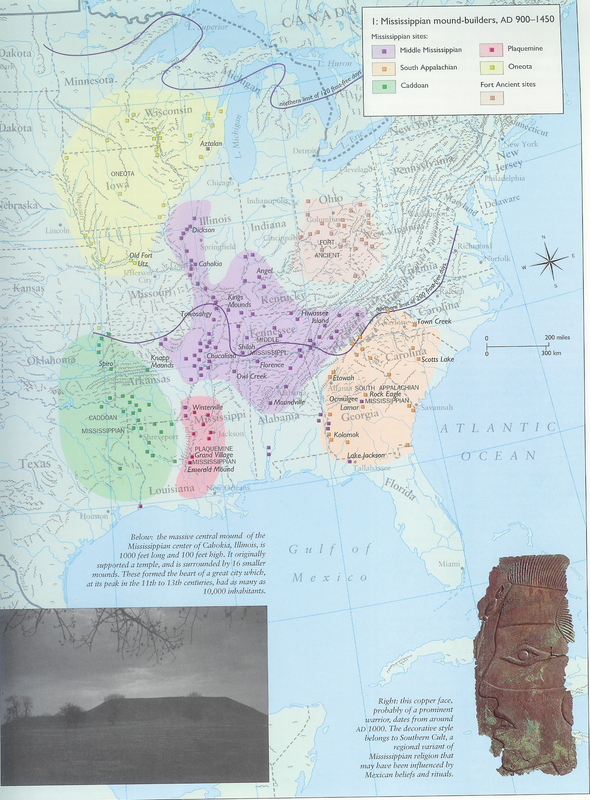

From c. 500 B.C. to c. 1650 A.D., the Adena, Hopewell, and Fort Ancient Native American cultures built mounds and enclosures in the Ohio River Valley for burial, religious, and, occasionally, defensive purposes. They often built their mounds on high cliffs or bluffs for dramatic effect, or in fertile river valleys. So common was the practice that the Ohio River Valley and its surrounding environs were once so populated with mounds that travelers such as Henry Brackenridge, passing through Ohio and the Mississippi Valley, could write in 1811: “There is hardly a rising town, or a farm of an eligible situation, in whose vicinity some of these remains may not be found." Modern urban expansion tragically decimated the mounds so that comparably few remain today.

Although archaeologists have learned much about these cultures, there is much historians do not, and may never, know. For example, we do not know how these cultures would have referred to themselves. The labels of Adena, Hopewell, and Fort Ancient are merely convenient identifiers based on three archaeological “type sites”, each of which held definitive cultural markers for each group. Despite the convenience of these labels, they are somewhat misleading, each indicating one solid group which lived closely together, spoke the same language, and practiced an immutable set of traditions with no account of regional variation. In fact, the people defined by each label were spread out over vast areas of land and spoke many different languages, often coming together only for trade or ceremonial purposes. Regardless, archaeologists and historians continue to use these terms, as will this exhibition, for simplicity’s sake.

The abundance of mounds captured the imagination of the European settlers who arrived in the United States from the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Although several European historians and scientists were willing to acknowledge, from comparatively early dates, the astonishing technical abilities of the Native Americas, many European settlers who encountered the mounds let their imaginations loose, willingly attributing their creation to almost all cultures save the Native Americans. Fortunately, during the nineteenth century, academic opinion slowly began to agree that various Native American cultures were responsible for the mounds, culminating in the work of the Bureau of Ethnology, created by John Wesley Powell, which silenced opposition in the academic community.

These three cultures represent only a small fraction of the Native American communities which thrived in Prehistoric Eastern America. Their skills and ingenuity regarding the landscape and the sky are mirrored in other Eastern native cultures and, indeed, across the prehistoric Americas.