Early Woodland Period - The Adena Culture

The Early Woodland period, which began in the Ohio River Valley about 1000 B.C., witnessed the introduction of several substantial lifestyle changes for some of its inhabitants, including: an increasingly sedentary lifestyle due to the cultivation of plants; more elaborate burial rituals which included the construction of conical burial mounds or elaborate earthworks; the introduction of pottery; and an enlarged trading network. The most prominent culture within the Early Woodland Period is the Adena, which was given its name by the archaeologist William C. Mills in 1902 after his excavations on the Adena plantation at Chillicothe revealed definitive cultural attributions which turned the location into a 'type site' against which all subsequent suspected Adena locations were compared.

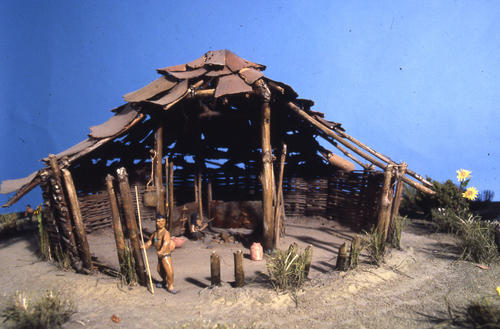

The Adena helped to initiate what is now known as the Eastern Agricultural Complex, a domestic farming revolution which allowed them to cultivate plants such as squash, sunflower, and pumpkins. Despite their growing interest in agriculture, they maintained a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, building temporary settlements which they returned to during the year.

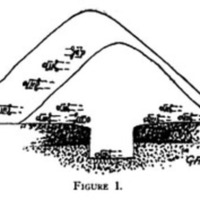

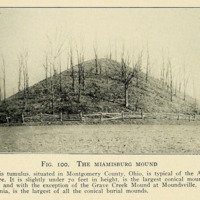

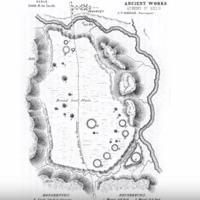

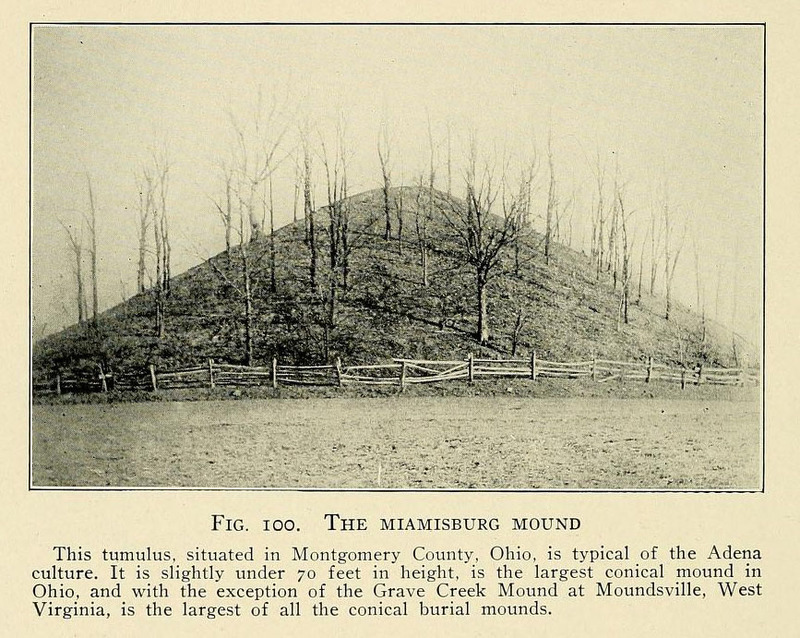

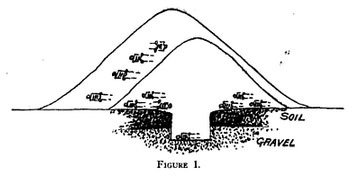

Perhaps the Adena culture’s best known activity is the creation of conical burial mounds. This represents a major change from comparatively subtle burial habits of the Archaic period when the dead were typically buried outside campsites with largely utilitarian grave goods. The Adena people built conical mounds and small circular earthen enclosures, which were typically built in prominent locations in the Early and Middle Adena cultures, often at the edges of river valleys, and served as public monuments. The Late Adena culture tended to cluster mounds together, such as in the Wolfe Plains Group. These structures, particularly the largest examples, were built up over many years as burials were stacked upon those of the initial inhabitants; in many cases the mounds could reach over thirty feet tall. Burial mounds were viewed as sacred, and are interpreted as communal sites where ceremonies, whether joyous or contemplative, were held.

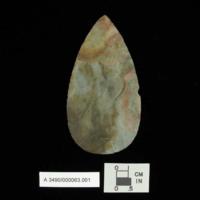

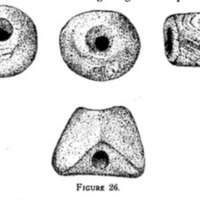

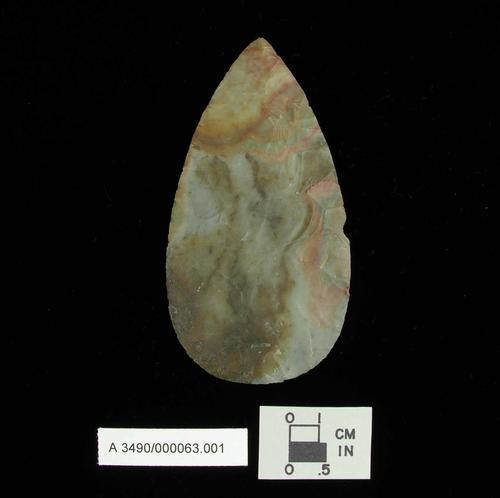

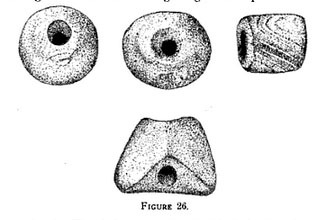

Despite their communal nature, only a select few, normally those of a privileged status such as shamans, were buried within mounds. Grave offerings reinforce this idea, with high-status goods such as elaborate personal adornments and artistic trinkets, although there have been burials uncovered in which no grave goods were found, indicating a lower-status individual. Evidence found within excavated mounds suggests that the remains were first buried in a wooden container then sprinkled with ochre or another colorful mineral before the mound was constructed over the remains. Occasionally, the wooden structure was first burned before the mound was built. However, it is important to note that not all Ohio Early Woodland burials involved mounds. In Northern Ohio, for example, Native American cultures chose to bury their dead in earthen enclosures, and there is evidence that the Adena occasionally adopted this trend in sites such as Seaman’s Fort in Erie County, Ohio.

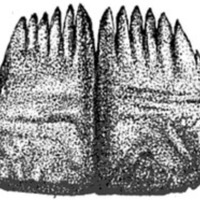

Another important trait of the Early Woodland Period in Ohio is the commencement of pottery in this region. Prior to its introduction, cooking was a comparatively difficult task involving hot stones dropped into waterproofed bowls. Pottery allowed for cooking directly over an open fire, which reduced the necessary cooking time. Its decoration was largely plain, though most Adena-style pottery was thick-walled with straight sides, with a conical base and a relatively wide mouth.

Although trade networks were used during the Archaic period, they grew under the Adena. Copper from the Great Lakes, marine shell from the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, and mica from the southern Appalachian Mountains have been discovered in grave goods. This may have reflected a growing desire to connect with distant tribes for social reasons, and certainly allowed community leaders to emphasize their personal status. Trade routes were another way for the Adena culture to spread its artistic and burial styles: several mounds in Canada and New York were clearly modeled on those of the Adena.