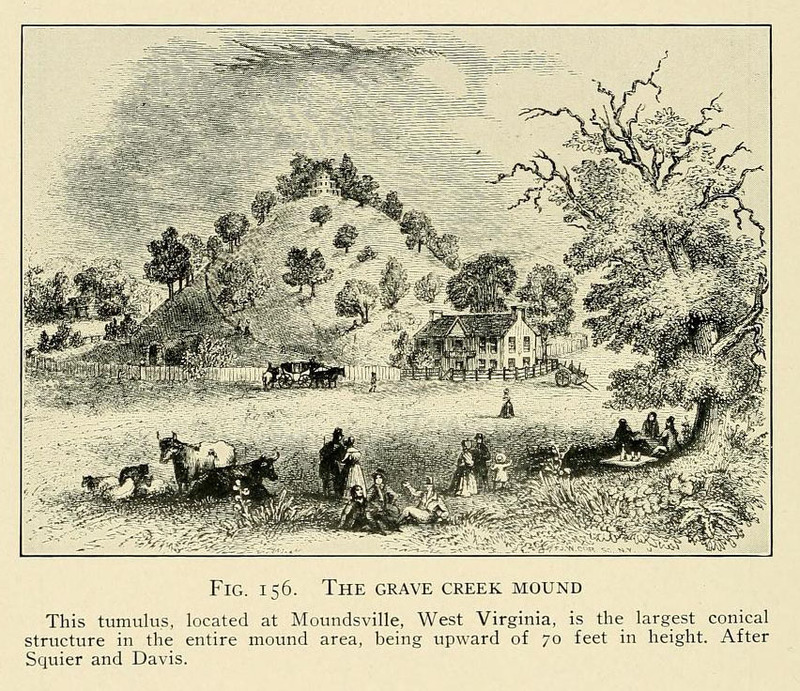

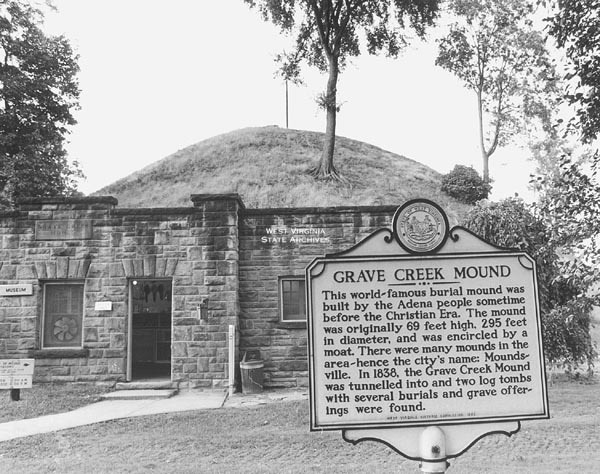

Grave Creek Mound

Grave Creek Mound, c. 69 ft tall and 900 ft in circumference, is the tallest conical mound in North America. The mound has a long, entwined history with European settlers. In 1770, Joseph Tomlinson was the first recorded European to discover its location. 1796, the English astronomer Francis Bailey examined the mound and interviewed local Native Americans, who, no longer descendants of the mound building cultures, had no collective memory of its use or function. Bailey, dissatisfied, wrote that a different race must have built the mounds “…for the present Indians know nothing about their use, nor have they any tradition concerning them.”

In 1803, the explorer Merriweather Lewis visited the mound and wrote: “This remarkable mound of earth stands on the east bank of the Ohio [river]…this mound gives name to two small creeks called little and big grave creek.”

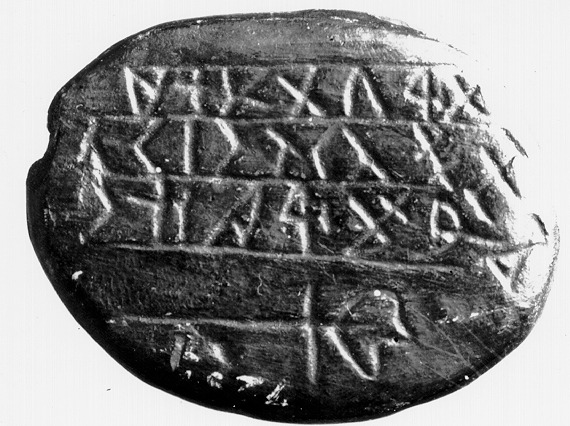

Grave Creek was first excavated in March, 1838 by descendants of Tomlinson. Although the excavation caused internal damage, due to the cross-channel tunnels dug within, the discoveries included burial chambers, skeletons, and grave goods. The Tomlinsons immediately opened the central mound as a museum. Though the Tomlinsons made an enduringly fascinating, and legitimate, discovery – the first discovery of log tombs from the Adena culture – this was to be overshadowed by the ‘discovery’ of a small, oval sandstone disk found in June, 1838. Three lines, written in an unknown alphabet, were etched upon its surface, and popular, and academic, imaginations were set aflame.

Contextually, the supposed discovery of the disk was popular not only because it fit into the concept that a ‘lost race’ built the mounds but because Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, had discovered the golden discs of Mormon only a few years earlier, and the discovery was fresh in everyone’s minds. Smith’s recorded “Nephites” were interpreted by many to have been the ‘lost race’ who built the mounds and who were destroyed by the ‘red-skinned Lamanites’, otherwise interpreted as the present Native Americans. Indeed, Orson Pratt, a Mormon convert, wrote in 1851 that this history was a ‘satisfactory’ answer to why there were so many burial mounds across America.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, self-professed leading expert on Native American history, was one of many who attempted to interpret the Grave Creek tablet. His conclusion, after a study in 1842, was that at least four letters resembled the ancient Celtic alphabet; he sent copies of the text to European scholars, whose translations ranged from Phoenician, Greek, Libyan, or Numidian.

Unsurprisingly, the surviving ‘translations’ are nonsensical, including:

1857, Maurice Schwab of France: “The Chief of Emigration who reached these places [or this island] has fixed these statutes forever.”

1860s, Jules Oppert: “the grave of one who was assassinated here. May God to avenge him strike his murderer, cutting off the hand of his existence.”

1875, M Levy Bing: “What thou sayest, thou dost impose it, thou shinest in thy impetuous clan and rapid chamois.”

Recent archaeological theory suggests that James Clemens, a local doctor, planted the tablet in the hopes of keeping popular interest in the mound. This was not known at the time, and academic interest remained vivid and divided over its authenticity through the nineteenth century.

Despite this attempt to keep popular interest fueled, interest lagged until finally the summit of the mound was converted into a Confederate fort during the Civil War. Today, it survives largely unchanged due to the conservation efforts of the Daughters of the American Revolution, who rallied to conserve it in the early twentieth century. Although the early excavation revealed a great deal of interest and information, Grave Creek still retains many unanswered questions which must remain unanswered unless and until further excavation is pursued.